To be listed on the haciendadelalamo TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

A Moorish morning out in Orihuela

Suggested routes in Orihuela: Route 1, following the Moors

Every area is defined by those who inhabited it, and although Orihuela is filled with rich Mediaeval and  Baroque monuments, the outline structure and core identity of the city relate to its 500 years of Moorish occupation.

Baroque monuments, the outline structure and core identity of the city relate to its 500 years of Moorish occupation.

Tracing the footprint of the Moors in Orihuela offers an enjoyable themed morning out for those with an interest in history, this being a route which can be followed at your own leisure at little cost, leaving time and a budget to enjoy a meal out at the end of an enjoyable morning in the city.

This route focuses on the Moorish elements of Orihuela: the historic Palmeral, the castle, the wall which surrounded the city, and the fiestas dedicated to this important period in the history of Orihuela.

A bit of history.

Most of the prehistory of Orihuela focuses around the fringes of the municipality in the more mountainous sierras and although the Romans had a substantial presence in the area, documenting what is now Orihuela as Orcelis, the major growth of the modern town began with the Visigoths who invaded following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th century. ( See History of Orihuela)

The Visigoths built a settlement called Aurariola on the site of modern day Orihuela, which included a  substantial fortified structure on the rocky outcrop of the Sierra de Orihuela, overlooking the River Segura, which was navigable at this time, and the flatlands of the Vega Baja down to the sea, controlling the important trade routes and the former Roman road, the Via Augusta, which ran right along the Spanish coast, into France and joined with other thoroughways along the Mediterranean basin. However, population numbers were low, as this was a time of war and armed struggle between the Visigoth rulers following the fall of the Romans, and constant threat of invasion from other Germanic tribes.

substantial fortified structure on the rocky outcrop of the Sierra de Orihuela, overlooking the River Segura, which was navigable at this time, and the flatlands of the Vega Baja down to the sea, controlling the important trade routes and the former Roman road, the Via Augusta, which ran right along the Spanish coast, into France and joined with other thoroughways along the Mediterranean basin. However, population numbers were low, as this was a time of war and armed struggle between the Visigoth rulers following the fall of the Romans, and constant threat of invasion from other Germanic tribes.

The settlement of Aurariola was ruled by Visigoth overlord Teodomiro, or Tudmir, but no real evidence has been discovered of Visigoth construction other than the wall which surrounded the fortification, the main growth of the town beginning when Moors and Berbers invaded what is now southern Spain in 711.

In practically no time at all, the major population centres had either been overrun or surrendered to the armed  onslaught. Although the Moors were formidable fighters allowing their opponents to surrender was their preferred route to domination, allowing them to achieve political power in a stable community in return for allowing the natives to carry on with their way of life to a large degree, thus ensuring greater economic prosperity and increased taxation revenue.

onslaught. Although the Moors were formidable fighters allowing their opponents to surrender was their preferred route to domination, allowing them to achieve political power in a stable community in return for allowing the natives to carry on with their way of life to a large degree, thus ensuring greater economic prosperity and increased taxation revenue.

This was the case in Aurariola and the Pact of Tudmir was signed on 5th April 713, by Tudmir (or Theodomir/ Teodomiro ) and Abd el Aziz, the son of the governor of Northern Africa, leaving Tudmir in power to continue ruling the wide swathe of territory which included the cities of Lorca, Mula, Orihuela, Alicante and Villena, but under the supervision of Abd el Aziz .

This pact lasted for two generations, until the area known as the Cora of Tudmir became a province of the kingdom of Al Andalús, “Uryula” (Orihuela) among the most important settlements: many even believe it to have been the capital of the territory, but unfortunately little documentation has survived and it has not been possible to prove or discount this notion.

In the ninth century, the Cora of Tudmir was absorbed into the Umayyad Caliphate, and then successively into other Arab provinces and kingdoms until the 13th century, constantly being passed back and forth between the Coras of Murcia (Mur-siya) and Valencia.

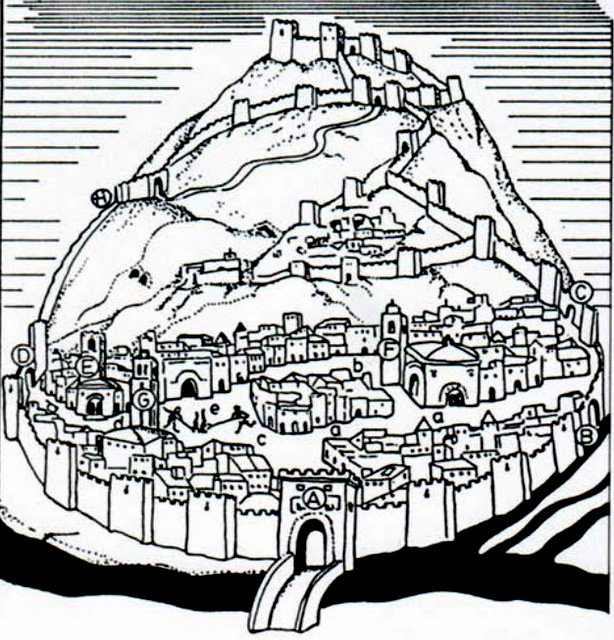

During this period the original Visigoth walls were rebuilt and extended, encircling the town inside a protective solid structure, leading all the way down from the castle ( the alcazaba) to the riverbank of the river Segura, and the town became an extensive Moorish stronghold, with a bridge, fortified gates, baths, bazaars and residential dwellings, surrounded by a lush Palmeral and irrigated farmlands. There were two walls, one encircling the castle, and the second, the town below it, both interlinked, with a series of entry gates and towers.

However, after 500 years of Moorish domination, the Christian forces of the Reconquist, spearheaded by the  powerful Kingdoms of Castile y León and Aragón, gradually re-took Spain from the invaders, and on 17th July 1243, Castilian troops led by Prince Alfonso, who was later to become King Alfonso X (“The Wise”), entered the city and conquered it: the date of this event still celebrated as a holiday throughout the municipality.

powerful Kingdoms of Castile y León and Aragón, gradually re-took Spain from the invaders, and on 17th July 1243, Castilian troops led by Prince Alfonso, who was later to become King Alfonso X (“The Wise”), entered the city and conquered it: the date of this event still celebrated as a holiday throughout the municipality.

Again, the policy of peaceful surrender was adopted, the local Moorish ruler remaining in situ until 20 years later when a rebellion by the Moors took place. They were angry at the failure of Alfonso to respect the terms of the treaty and took up arms against Alfonso in collaboration with Moorish settlements in other parts of the area including neighbouring Murcia, but were quashed ruthlessly by his father –in-law , Jaime I of Aragón, who sent a sizeable army to deal with the rebellion. After that, Moors were not allowed to live within the protection of the city, although were allowed to stay and continue farming, providing food for the growing cities, as long as they at least pretended to renounce their own religion and become Christians. This situation lasted until 1492 when the last Moorish Kingdom in Spain, Granada, fell to the forces of Isabella and Ferdinand, “the Catholic Monarchs” who expelled all Moors from Spain.

The route:

Driving into Orihuela from the motorway, follow signs for the city centre via the N-340. The road climbs up through the Sierra de Orihuela, with the famous climbing rockface of the “pared negra” or black wall on the right hand side, and just before entering the tunnel through the rock is a viewing point and parking for those who would like to walk down into one of Orihuela’s most important Moorish remains: the Palmeral. Crossing the road across a solid white line is illegal, so either carry on through the tunnel, around the first roundabout and back again, or stop off at this viewing point in the afternoon after lunch on the way back.

The Palmeral, Orihuela

The Palmeral is the second largest in the whole of Spain and unique in that it is the same size now as it was  over 1000 years ago when the population of this area were Moorish and Berber invaders from Africa, a period which lasted from 711 to 1243.

over 1000 years ago when the population of this area were Moorish and Berber invaders from Africa, a period which lasted from 711 to 1243.

The palmeral is an agricultural ecosystem which is perfectly designed to take advantage of the unique conditions for agriculture in Spain, using nature to solve the problems encountered in this type of climate. The growing area is divided into plots using palm trees around the borders of each plot, with irrigation channels in between. The tall palms give shade, as well as providing an abundance of natural materials which are used for a huge range of everyday uses, as well as supplying dates, an essential foodstuff .

In their shade, fruit trees can be grown, and in turn, other crops in the shade of the fruit trees, dealing with the issue of burning sun which would otherwise make it impossible to farm in the intense Spanish heat. The survival of this historic palmeral is due to the fact that even after the Moors were ejected fully from Spain in the 15th century, the success of the palmeral guaranteed that farmers continued to farm it, and indeed today, crops are still grown under the protective shadow of the Orihuela palmeral. ( Click for more information, Orihuela palmeral).

Continue on towards the town, turn left at the roundabout and then follow the road down past the Ociopea shopping centre, parking behind the centre. Facing the city, with the shopping centre behind you, there is a  small section of the original Moorish city wall still visible in the left hand corner of the carpark, and looking up, the structure of the original Moorish castle is visible on the skyline. At one point the wall encircling the city ran straight down the side of the Sierra above you, linking these two structures, then carried on right the way across the foot of the city, a huge structure which would have offered protection for farmers and their livestock, as well as created a secure and imposing structure from which to administer the settlement.

small section of the original Moorish city wall still visible in the left hand corner of the carpark, and looking up, the structure of the original Moorish castle is visible on the skyline. At one point the wall encircling the city ran straight down the side of the Sierra above you, linking these two structures, then carried on right the way across the foot of the city, a huge structure which would have offered protection for farmers and their livestock, as well as created a secure and imposing structure from which to administer the settlement.

From here, walk down through an alleyway at the back of the houses and emerge in a shaded plaza next to the municipal library, “Maria Moliner”, in Calle Hospital. Turn right and half way down this street is the municipal archaeological museum, the Museo Arqueológico Comarcal de Orihuela, located in the complex of the Hospital San Juan de Díos.

Municipal Archaeological Museum, Orihuela

This little museum contains an eclectic mix of artefacts recovered from the various archaeological sites  throughout the municipality, including a Moorish tomb and several pieces of intricate ceramics and fretwork mouldings from residential dwellings. There are other interesting exhibits which have no relation to the Moors, including the striking sculpture of La Diablesa by Nicolás de Bussy, which is still paraded through the streets of Orihuela on Good Friday, and is well worth seeing. Click for more information about the Archaeological Museum, Orihuela.

throughout the municipality, including a Moorish tomb and several pieces of intricate ceramics and fretwork mouldings from residential dwellings. There are other interesting exhibits which have no relation to the Moors, including the striking sculpture of La Diablesa by Nicolás de Bussy, which is still paraded through the streets of Orihuela on Good Friday, and is well worth seeing. Click for more information about the Archaeological Museum, Orihuela.

Opening hours of the museum:

Tuesday to Saturday 10.00 to 14.00 and 17.00 to 20.00, Sundays and public holidays 10.00 to 14.00.

Closed on Mondays, Admission free of charge

From here, turn right out of the museum, continuing down towards the attractive plaza in which the town hall is located, the Plaza Carmen. This charming plaza is home to the Monastery of El Carmen, which is generally closed, but offers welcome shade during the hot months. If you’re lucky enough to find the door open , go in, there’s a rare sculpture by Francisco Salzillo inside which survived the devastation and burnings prior to the onset of the Spanish Civil War. The town hall occupies the former Palacio del Marqués de Arneva, the escudo bearing the family coat of arms, one of the most impressive carved escudos in Orihuela, facing the barrio of Rabaloche ( the district from which you have just come) on the corner of the building. It really is worth stopping to look at.

Just on the corner facing the town hall is the church of saints Justa y Rufina, two of the patron saints of Orihuela, a Gothic gem, being one of only two such gothic towers surviving in the Valencia region, the other being on Valencia cathedral itself. Although it’s tempting to peek inside, ( save it for the monumental morning out, or click Iglesia Santas Justa y Rufina )have a look at the tower with its Gothic gargoyles and clock as you pass : this clock is believed to be the oldest church clock still working in Spain, then carry on around the front of the church and bear right into an attractive cobbled plaza with impressively pruned trees, Plaza Togores.

Running along the back of the plaza is the sleek modern building of the Orihuela Miguel Hernández University, and in the corner of the plaza a set of stairs leads down to the Museo de la Muralla, a museum housing the remains of the vast Moorish fortification and protective wall which surrounded Orihuela during the

period of Moorish occupation.

Museo de la Muralla

This museum houses the remains of part of the defensive wall which surrounded the city, along with several  Moorish houses and their typical format of rooms clustered around a central courtyard, an original Moorish bath-house which covered 200 square metres and the remains of a Gothic palace built in the 14th century, the only civic Gothic building yet found in Orihuela. The sheer scale of the wall itself can clearly be seen, giving an idea of just how substantial these fortifications really were. The museum has an interesting audiovisual which gives a better idea of what’s inside this museum, and images giving a clearer picture of just how substantial the walled structure would have been, as well as a collection of ceramics and artefacts recovered from the excavations. Once the site had been excavated, the new University building was built over the top of it.

Moorish houses and their typical format of rooms clustered around a central courtyard, an original Moorish bath-house which covered 200 square metres and the remains of a Gothic palace built in the 14th century, the only civic Gothic building yet found in Orihuela. The sheer scale of the wall itself can clearly be seen, giving an idea of just how substantial these fortifications really were. The museum has an interesting audiovisual which gives a better idea of what’s inside this museum, and images giving a clearer picture of just how substantial the walled structure would have been, as well as a collection of ceramics and artefacts recovered from the excavations. Once the site had been excavated, the new University building was built over the top of it.

Opening times:

Summer : 1st July to 31st August (Tuesday to Saturday 10:00am to 14:00 pm and 17:00pm to 20:00pm)

Winter: 1st September to 30th June (Tuesday to Saturday 10:00am to 14:00pm and 16:00pm to 19:00pm)

Sundays and festival days 10:00am to 14:00pm, Closed on Mondays

Entry: Free of charge

More information and map, Museo de la Muralla.

From the museum, return to the front of the church of Justa y Rufina, and then back into the Plaza Carmen facing back towards the Archaeological museum, but this time, take the road running right off the roundabout, running parallel to Calle Hospital, Calle Francisco Die.

Just a short distance up this street is an open space with a tiled seating area and water feature, which we´ll return to after one more stop, then in the next block of houses along is the next location: The Museo de la Reconquista.

Museo de la Reconquista, Calle Francisco Die

This is the museum run by participants in the annual Moors and Christians Fiestas, which take place every  year around the 17th July and features some of the more spectacular costumes and a historical overview of the events which culminated in the Moors being expelled from Spain.

year around the 17th July and features some of the more spectacular costumes and a historical overview of the events which culminated in the Moors being expelled from Spain.

Also included are weapons and musical instruments in the style of those used during the period of the Reconquista, and paraphernalia associated with the processions and fiestas of the city, which have been held every year since 1974. There is also a painting and explanation of the legend of La Armengola, ( see below) which lies behind the liberation of Orihuela almost 800 years ago and plays an important part in the Fiestas every year.

Opening Times:

From Tuesday to Saturday between 10.00 and 14.00 and again from 16.00 to 19.00, as well as on Sunday mornings from 10.00 to 14.00. From 1st July to 31st August the afternoon timetable is put back one hour.

Entry free of charge.

click for map and further information, Museo de la Reconquista, Orihuela

Pozo del Crémos

Coming out of the museum, turn left and back to the water feature. This is the Pozo del Crémos and the tiled  decoration recounts the legend of the Armengola, which relates to the turbulent period of uprising which took place 20 years after the Christian Reconquist, when Moors who had been born in this area, their families farming it for centuries, rebelled against the unjust and harsh laws and taxes imposed on them by the Christian invaders who had failed to live up to their promises.

decoration recounts the legend of the Armengola, which relates to the turbulent period of uprising which took place 20 years after the Christian Reconquist, when Moors who had been born in this area, their families farming it for centuries, rebelled against the unjust and harsh laws and taxes imposed on them by the Christian invaders who had failed to live up to their promises.

According to tradition, Benzaddón, the local ruler of Orihuela, lived in the castle and in the village below was La Armengola, nursemaid to the children of Benzaddón, who although Christian could enter the fortress as and when she chose without being treated as a hostile agent.

Due to the harsh treatment meted out to the Moors by King Alfonso X, a series of plots were hatched to oust the Christian forces, and rebellions broke out across the conquered areas, King Alfonso calling for military support from his father in law, Jaime of Aragón. Benzaddón joined with the Moors from the Kingdom of Murcia to put the Christians to the sword, hatching a plan to attack on 16th July.

However, La Armengola caught wind of the plot and told her fellow Christians about the plans to slaughter them all. Deciding to strike first, she dressed two strong young men named Ruidoms and Juan de Arnúm in the clothes of her daughters, and took them into the citadel, along with her husband, where they hid until nightfall and took the guards by surprise on the eve of the festival of Saint Rufina and Saint Justa. Legend recounts that the figures of the two saints appeared as lights in the sky, illuminating the skirmish between the four Christians and their Moorish opponents. Armengola herself took up arms and joined the struggle, showing enormous courage and strength, and between the four of them they managed to kill the guards and  Benzaddón before placing the symbol of the cross of Christianity on the highest battlement of the fortress.

Benzaddón before placing the symbol of the cross of Christianity on the highest battlement of the fortress.

Their acts co-incided with the arrival of King Jaime’s army, foiling the plot to murder the Christians, and for this reason the fiesta to celebrate the freedom of the city from the clutches of the Moors is held on 17th July.

The night before the main fiesta lanterns are lit on the ruined battlements of the castle, and on the day itself the town council dress up in all the festive paraphernalia and carry the city’s banner to a solemn Holy Mass which is held in the church devoted to Santa Justa and Santa Rufina. Here the tale of Pedro Armengol’s wife is re-told every year.

Moving upwards.

From here, it is possible to either walk up alongside the Pozo de Cremós, and on up to the castle on foot, or return to the car and drive half way up, which is a little complicated to explain, but basically requires crossing over the bridge nearest to the shopping centre, turning left parallel to the river, then back over the next bridge and straight up to the seminary, where there is parking.

From there the walk up to the Moorish castle itself is quite steep, over an unmade path, but it is possible to walk right up to the old castle ruins on the top of the hill above Orihuela, with fantastic views across the Vega Baja, and down onto the historic Palmeral below.

When the Ed was researching this route the preferred option was to walk up alongside the Pozo to see the views over Orihuela, then return down to the streets below to enjoy a good lunch, before driving up to the half way mark and walking off the substantial portion of Arroz con Costra by climbing up to the Moorish castle.

Those with lesser mobility may enjoy driving up to admire the view and then heading down into the palmeral below by car.

Orihuela castle

See more information about the castle, including how to drive up there and safety recommendations.

There is no documentary evidence to indicate when the castle was first built, other than that it dates from the period between 711 and the tenth century. What is certain is that during this period a substantial protective fortification was erected, an alcazaba, and the castle incorporates many typical Moorish features, including a large embalse, or water storage tank and subterranean aljibe, a water storage unit. Many of the walls remaining today were constructed using Moorish building techniques, which involved creating a shuttering filled with rocks and rubble into which a liquid mixture was poured. Moorish walls are very distinctive as the peg holes can clearly be seen left by this building method.

There is no documentary evidence to indicate when the castle was first built, other than that it dates from the period between 711 and the tenth century. What is certain is that during this period a substantial protective fortification was erected, an alcazaba, and the castle incorporates many typical Moorish features, including a large embalse, or water storage tank and subterranean aljibe, a water storage unit. Many of the walls remaining today were constructed using Moorish building techniques, which involved creating a shuttering filled with rocks and rubble into which a liquid mixture was poured. Moorish walls are very distinctive as the peg holes can clearly be seen left by this building method.

In the tenth century Abd-al-Rahman III al-Nasir, mentioned the castle in documentation, saying it was a “strong castle surrounded by orchards and gardens with bazaars , and a bridge across the river“.

In the Mediaeval era the castle was a strong and important fortification and was attacked during what is known as the “War of the two Pedro’s” between the kings of Castile and Aragón in the second half of the 14th century. Pedro I (“The Cruel”) of Castile unsuccessfully attacked the castle in 1364, although he gained revenge and stormed it two years later. ( Apparently lack of food forced the surrender, those inside having been forced to resort to cannibalism to survive).This success was short-lived, though, and Pedro IV (“The Ceremonious”) of Aragón re-took it not long afterwards.

Pedro incorporated Orihuela into the territory of Valencia, maintaining its status as a frontier territory in relation to its near neighbours in Murcia (which belonged to the kingdom of Castile) and bordered with Granada (the only Kingdom still under Arabic rule), increasing the status of the town and the castle and due to its strategic importance Orihuela was finally declared a city on 11th September 1437.

In 1521 Orihuela was sacked after the city’s population rose up against Carlos I in 1518, the battle of Bonanza ensuring the city was severely punished for its disloyalty. From this point on, its strategic importance declined and the structure of the castle started to suffer.

In the Wars of Spanish Succession at the start of the eighteenth century the city’s governor, the Marqués de Rafal, threw in his lot with Charles of Austria, ensuring that Orihuela ended up on the losing side. When his opponent Felipe of Borbón triumphed, the city was sacked again and lost its privileges.

During the conflict the castle was struck by lightning and the gunpowder stored inside exploded, not only killing the unfortunate soldiers garrisoned in the castle, but also completely obliterating the main structure of the castle itself.

In March 1829 the “Torrevieja earthquake” caused severe damage in the town and the last remains of the castle were destroyed, along with many important buildings across the whole of the Vega Baja.

Since then, it has continued to crumble, and little remains today other than a few scraps of the walls and bases of the towers.

Click for more information about Orihuela Castle

Final note.

If you are unfamiliar with Orihuela city, it may be worth walking to the tourist office first in order to collect a map. From the suggested carparking location, follow the instructions to the archaeological museum, then straight down to the town hall, and carry on straight alongside the church of Justa y Rufina. Keep going straight and you´ll pass the cathedral. The tourist office is in a plaza just past the end of the cathedral on the left hand side. Click Orihuela Tourist office.